As I quoted back in 2007, as early as 1846 a story circulated about Gen. George Washington reading aloud the 101st Psalm as he took command of the Continental Army. The Rev. Daniel Waldo (shown here) told that story at an Independence Day gathering in Westfield, and it was picked up by the Abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator. Waldo was a Revolutionary veteran, but he wasn’t in the army in 1775 and never saw Washington.

As I quoted back in 2007, as early as 1846 a story circulated about Gen. George Washington reading aloud the 101st Psalm as he took command of the Continental Army. The Rev. Daniel Waldo (shown here) told that story at an Independence Day gathering in Westfield, and it was picked up by the Abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator. Waldo was a Revolutionary veteran, but he wasn’t in the army in 1775 and never saw Washington.

In 1872 Harriet Beecher Stowe retold the tale in one of her books through the voice of a fictional character. In 1878 the Farmer’s Cabinet magazine quoted a description of the event, said to have taken place on 2 July 1775. The reported eyewitness was the late Amherst, New Hampshire, farmer Andrew Leavitt:

After the officers had succeeded in getting the men into tolerable order, Gen. Washington came upon the field and reviewed them [the soldiers], he was a large noble looking man, apparently in the full strength of manhood, mounted upon a magnificent black horse, in whose shining coat you could almost see your face, so carefully was he groomed. After the review the soldiers gathered around the tree under which the General sat, and listened to his address. At the conclusion he read to them from his Psalm book the 101st Psalm.

The local historian who wrote that passage said he’d heard the story from Leavitt about 1842. Descendants of another veteran from the same company, Joseph Wallace, recalled him

telling a similar anecdote.

Leavitt and Wallace were in Capt. Josiah Crosby’s company in Col. James Reed’s New Hampshire regiment. On 21 June, according to that state’s

Provincial and State Papers, that whole regiment was camped at Winter Hill in modern Somerville, and they seem to have stayed there. There’s no evidence that they were pulled away from the front line so that Gen. Washington could review them on

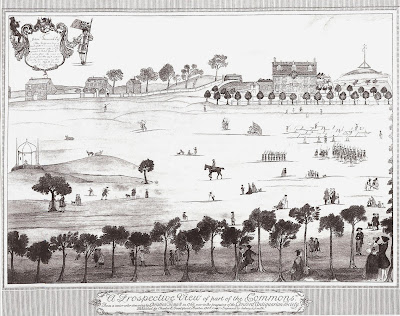

Cambridge common. On the other hand, those two psalm-singing stories didn’t actually claim that event took place on the common, or that the “tree under which the General sat” was the

Washington Elm.

The big problem with that tale is that anyone who’s studied Washington recognizes that it would be completely out of his usual pattern to sit under a tree and read a psalm to soldiers gathered around him. He valued hierarchy and rank, especially when he first arrived in Cambridge. His religious behavior was not demonstrative. His main concern on arriving in Massachusetts was to review and strengthen the siege lines.

This sort of behavior might make sense coming from Gen.

Artemas Ward or some other New England officer who valued his work as a church deacon. From the new, closely-watched Virginian commander-in-chief the act would have been remarkable—yet nobody remarked on it for more than seventy years.

Another religiously tinged account of Washington taking command appeared in

The Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, published in 1864 by a minister named Benjamin Franklin Morris. Morris claimed to quote “from the journal of a chaplain in the American army”:

July 4th, 1775.—I have seen the new general appointed by Congress to command the armies of the colonies. On seeing him I am not surprised at the choice. I expected to see an ardent, heroic-looking man; but such a mingled sweetness, dignity, firmness, and self-possession I never before saw in any man. The expression “born to command” is peculiarly applicable to him. Day before yesterday, when under the great elm in Cambridge he drew his sword and formally took command of the army of seventeen thousand men, his look and bearing impressed every one, and I could not but feel that he was reserved for some great destiny.

Even among ardent Patriots around Boston, this would be an enraptured description of Washington.

Morris never stated the name of this chaplain. The manuscript has never surfaced. No other author that I’ve found has relied on that journal entry. The diary says the event took place on 2 July (“Day before yesterday”), but authentic contemporaneous sources indicate that Washington and Gen.

Charles Lee arrived in Cambridge that day in the middle of the afternoon, when it was raining. The traditional date for Washington taking formal command or reviewing American troops is 3 July.

Morris obviously wrote his book to argue that Christianity underpins the government of the United States—a familiar claim today. He seems to have been overly credulous about, or simply invented, a quotation to support his position—again, a familiar situation today. And Morris’s book is

still being cited by people who share its core idea.

COMING UP:

George Washington’s treehouse.

The journalist J. Benson Lossing came through Massachusetts in 1848 on an assignment for Harper’s Magazine. He was dogged in looking for elderly survivors of the American Revolution and setting down their stories. On the other hand, he had a tendency to print legends without apparently inquiring too deeply into them.

The journalist J. Benson Lossing came through Massachusetts in 1848 on an assignment for Harper’s Magazine. He was dogged in looking for elderly survivors of the American Revolution and setting down their stories. On the other hand, he had a tendency to print legends without apparently inquiring too deeply into them.