Meanwhile, in London…

This change had nothing to do with the unhappiness in America. It was all about the internal politics of the royal court, and in fact of the royal family. But as a result, the man who had championed the Stamp Act was removed from power. George III invited the Marquess of Rockingham to form a coalition with a broader base.

The American press speculated happily that this change meant the popular William Pitt would return to a position of authority. In fact, Pitt refused any role in the new government.

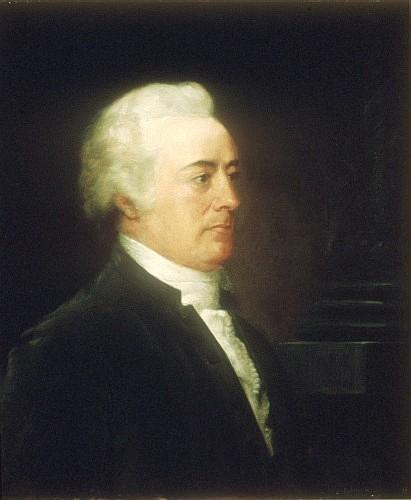

Instead, the strongest man in the new coalition was Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland, the king’s uncle and a military commander (shown above). Cumberland hosted the cabinet meetings at his city and country estates.

The first news those ministers received about the violent American protests was a letter from Massachusetts governor Francis Bernard, sent on 31 August and received on 5 October. Two days later, Andrew Oliver’s resignation as Massachusetts’s stamp master arrived. The government’s quick response was to send back a letter urging Bernard to appoint a temporary stamp-tax collector and proceed as planned.

The cabinet met on 13 October and had a brief discussion of the situation in North America, among many other things, according to John L. Bullion’s study in the 1992 William & Mary Quarterly. The ministers were confident that the leaders of colonial society would realize that they had to use stamped paper for lawsuits, transatlantic trade, and their other business, so they would soon accede to the new law, however grudgingly.

The Privy Council issued instructions to the colonial governors on 23 October, urging them to repeat that message about the wisdom of accepting the tax and getting on with business. Those governors could call on the military forces available in North America to put down riots, if necessary. But there was no plan to send more troops across the ocean; that would be expensive (the Stamp Act was supposed to bring in revenue, not cost a lot) and hard to do with winter coming on.

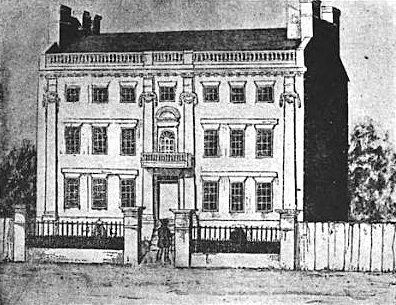

Five days after that message went out, a letter came in from Gen. Thomas Gage in New York. He reported that riots were spreading across the colonies, driving stamp masters into hiding and threatening the stamped paper itself. Gage suspected that rebellious Americans planned to make it impossible for royal officials to distribute the stamps and then to insist that courts and Customs offices stay open anyway. Now the situation seemed more dire. On 31 October, the cabinet gathered again at the Duke of Cumberland’s London house.

Just before the ministers went into their meeting, the duke collapsed with a heart attack and died. Though Cumberland had significant health problems, including an old war wound, he was only forty-four years old, and no one expected him to leave the scene so suddenly.

All the politicians in London began speculating and maneuvering anew. The Marquess of Rockingham was now the actual head of the government, as well as the titular one, but could he hold power without the duke’s authority behind him? In that political turmoil, the cabinet didn’t meet again until 11 December. And by then, they knew the situation in America had gotten worse.

.jpg)